“A picture is worth a thousand words” is perhaps one of the most popular sayings across the world. A single photo – or even a single drawing – can contain within itself an entire universe of meanings, emotions, and opinions. An image can open our eyes, mobilize us against an injustice, or turn us against our neighbor. The effect an image can have on us occurs both consciously and unconsciously. While some obviously state their intended meaning, others impact us in more nebulous and subtle ways. There are not enough studies with firm evidence about the effects that frequent exposure to images that convey certain ideas may have on the viewer. We may learn more over the next few years about how we internalize messages that we’re confronted with on a daily basis, and how it may be possible we internalize these messages without even realizing it.

Unfortunately, those aiming to promote hateful and polarizing ideas fully understand the power of images and the process of interpreting their meaning. These same actors are masters in the art of hiding their hatred, by using humor and irony in order to make the unacceptable deemed acceptable in the eyes of society (Pinilla, 2022).

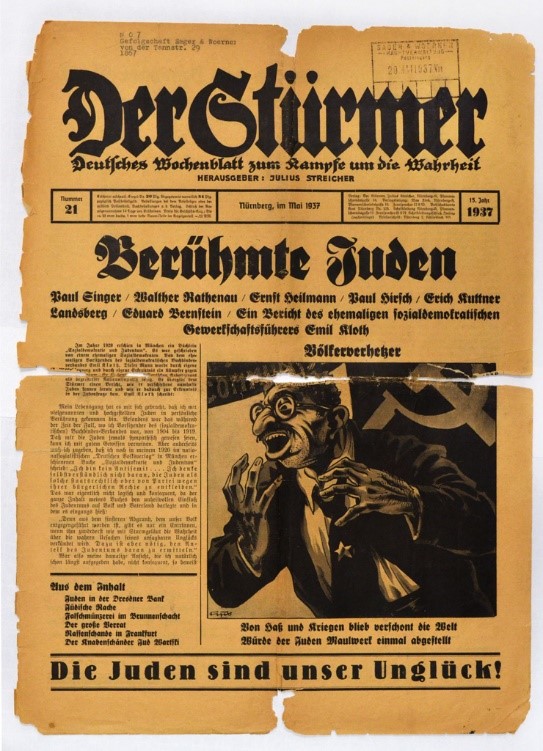

Social media channels are key disseminators of racist and white supremacist ideas At the turn of the 20th century, caricatures in the printed press played a similar role in the spread of antisemitic sentiment. Two caricatures that can be viewed at the Montreal Holocaust Museum, as well as on our website, clearly illustrate how easily drawings can spread antisemitism.

Presentation of Caricatures

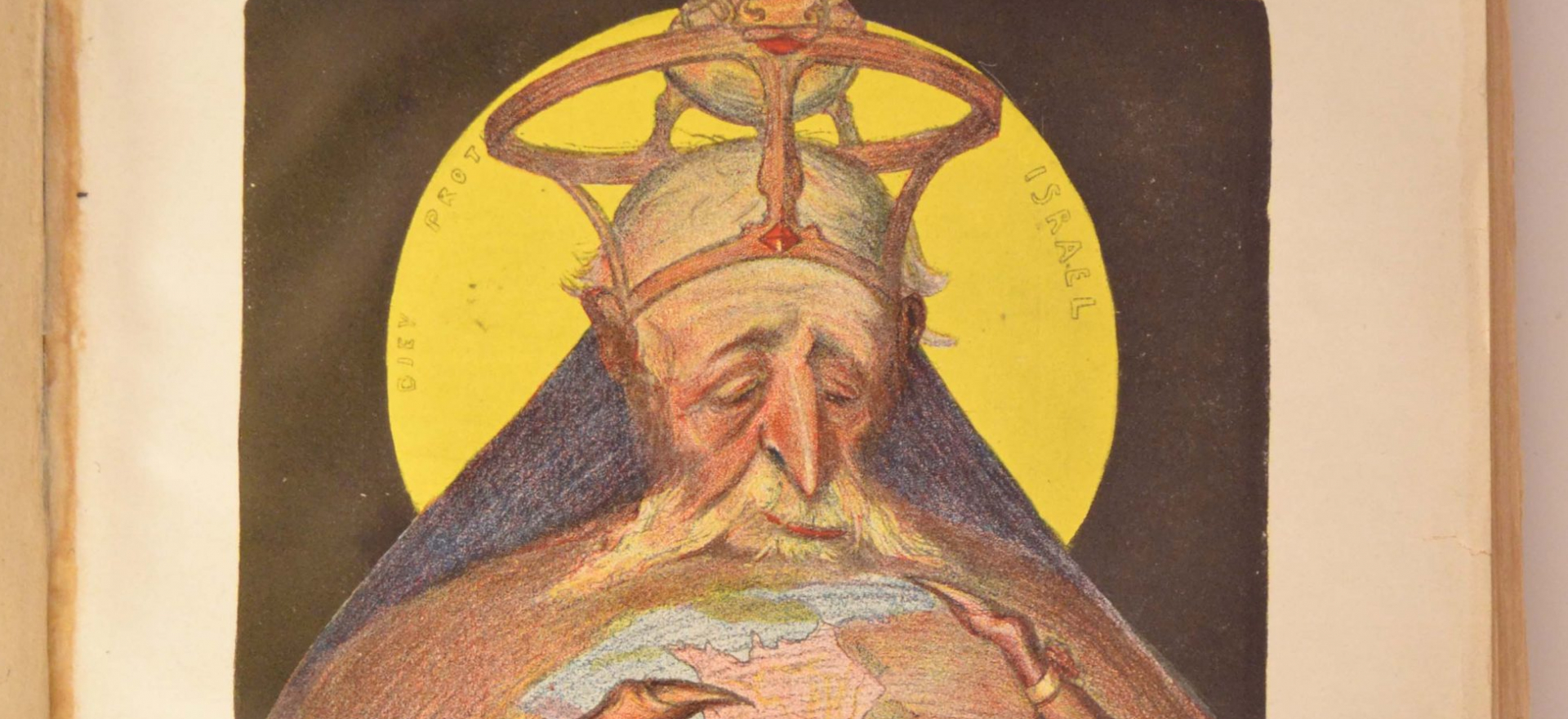

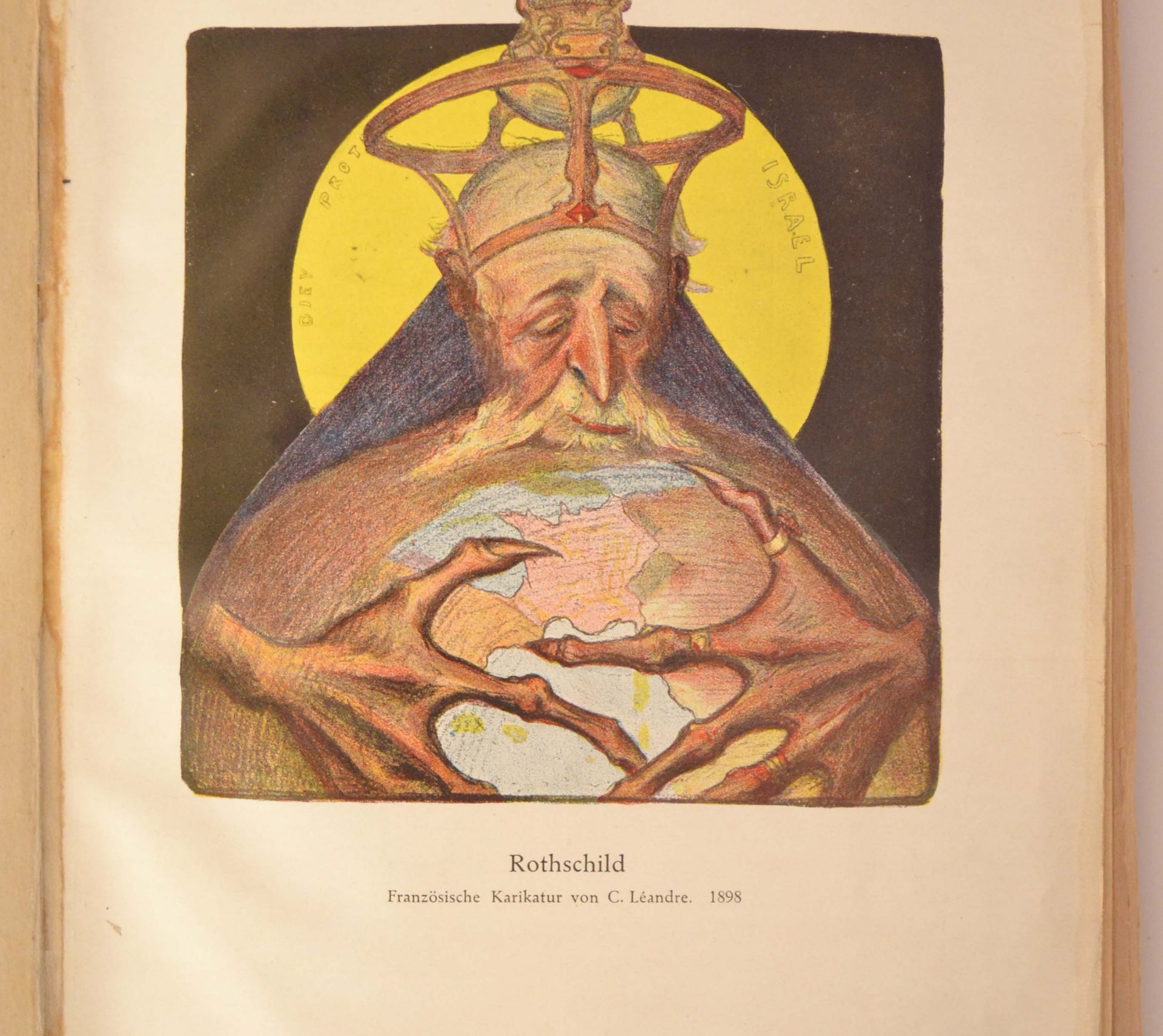

The “Rothschild” caricature (image 1), by Charles Léandre, was published in the French newspaper Le Rire in 1898. Without any clear editorial approach, this weekly humour publication included the work of antisemitic caricaturists, like Charles Léandre, as well as socialist or anarchist ones. The “Rothschild” caricature was reprinted in a book entitled Die Juden in der Karikatur (Jews in Caricature, 1921), an object that was loaned to the Montreal Holocaust Museum by Holocaust survivor Walter Absil.

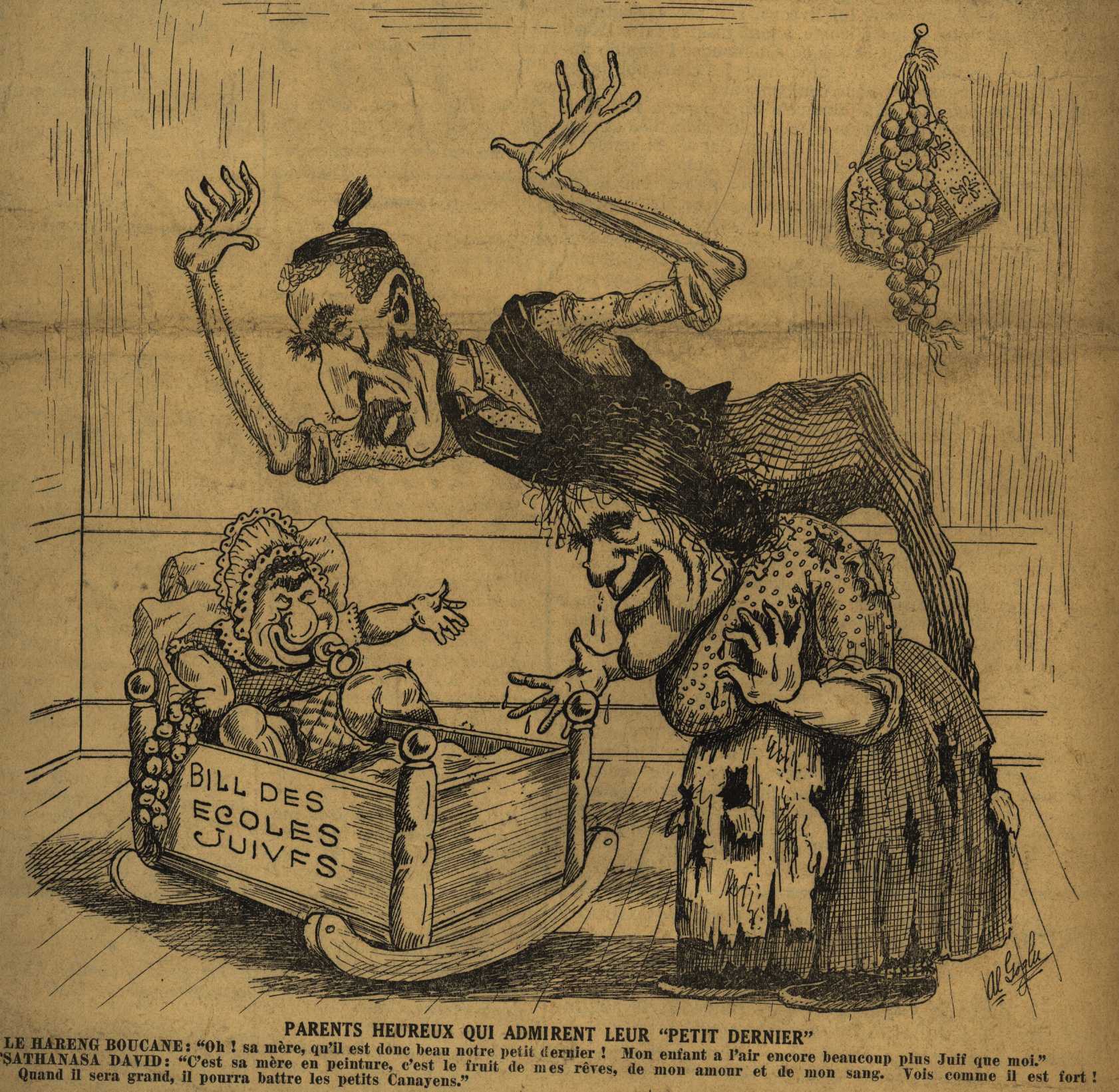

The “Happy Parents Admiring their Youngest” caricature (image 2) by Al Goglu (a pseudonym that was used for multiple authors, in this case Albert Labelle) appeared in Le Goglu, a Quebec newspaper in 1930 and is included in our Brief History of Antisemitism in Canada reference guide. Le Goglu, a weekly paper, was published between 1929 and 1933 by Adrien Arcand, the founder of the National Social Christian Party. This was a Canadian political party with Nazi ideas that was fundamentally antisemitic. The newspaper name already suggests its editorial policy: Goglu translated as bobolink, is a type of migrating songbird commonly found in Canadian and American fields. However, in Quebec at the beginning of the 20th century, the term was used figuratively to mean a funny individual or a bad joker. In this instance, the term “goglu” is being used to refer both to this bird and to the intended satirical tone of the publication. (Desforges, 2012)

MEDIA REVOLUTION AND DEMOCRATIC MOMENTUM

At the turn of the 20th century, during a media revolution described as the golden age of the press, antisemitic caricatures multiplied. Technical advances (paper made from wood pulp, along with the invention of continuous paper-making machines, the rotary press and linotype) made it possible to print cheap newspapers in large quantities. In the 1930s, Le Goglu claimed to be the “second largest newspaper in French America” following La Presse, with a (undoubtedly inflated) circulation of 85,000 copies per week (Desforges, 2012).

At the time, both France and Quebec were young democracies. Within this framework, they implemented laws that protected individual freedoms, such as the 1881 Freedom of the Press Act in France, or the 1929 Press Act in Quebec. These laws were very lenient and meant that almost anything could be written and published.

Finally, at a time when a large percentage of the population was still illiterate, caricatures were a highly popular way for newspapers to increase their circulation, which explains the proliferation of “humorous” weeklies such as Le Rire in France or Le Goglu in Quebec.

CARICATURES THAT DRIVE “ANTISEMYTHS” (Matard-Bonucci, 2001)

1. Medieval cultural heritage

Antisemitic caricatures at the turn of the 20th century used imagery that is deeply anchored in Western Christian culture. At the turn of the 13th century, medieval Church illuminations and sculptures began to depict Jews with a long nose (image 3). This exaggeration was intended to provide a visual distinction of the one who, according to the Catholic church, had betrayed God (Judas) and turned away from Christian values. These physical and character traits were deeply rooted in the European collective imagination. They can also be found in the iconography of certain medieval “monsters” such as witches and trolls who are also portrayed with long, hook-shaped noses.

2. Racist antisemitism

At the turn of the 20th century, antisemitic caricatures also drew on emerging pseudoscience, such as cranioscopy and physiognomy, to reinforce the alleged links between physical attributes and character traits. This led to frequent zoomorphism in the antisemitic caricatures, in which Jews were associated with the values attributed to certain animal species. Thus, Jews were often represented as birds of prey (image 1), snakes, octopuses, parasites, etc.

This zoomorphism was part of a racial and racist affirmation that excluded Jews from the so-called dominant race, as summarized by the caption that accompanies the Goglu caricature: “My child looks even more Jewish than I do.” (image 2)

3. The anti-national and globalist plot

Finally, at a time when national identities were being asserted, Jews were falsely perceived by antisemites as traitors to the nation. The Goglu caricature (image 2) emphasizes this anti-national character in two ways: On the upper right, the coat of arms from the Canadian flag is seen hanging hidden behind a braid of garlic, symbolizing disrespect for the symbol. At the bottom, the caricature’s caption states that Jews are a threat to the Canadian nation: “See how strong he is! When he grows up, he can beat the little Canayens”.

The “Rothschild” caricature (image 1) highlights the perpetually anti-national, globalist and capitalist conspiracy supposedly hatched by Jews. “Rothschild” is a popular antisemitic symbol of the rich and miserly Jew (the Rothschild family was a Jewish banking family in Europe at the time), whose alleged goal is to control the world through finances. The caricature clearly presents this vision of the Jewish threat in the way that Rothschild “encircles” the globe and threatens France with his “claws.”

CONCLUSION

At the turn of the 20th century, the proliferation of antisemitic caricatures, which were sometimes extremely violent in so-called humorous newspapers, facilitated the propagation of a radical antisemitic discourse. This discourse was taken up by the fascist and Nazi regimes in Europe in the 1930s and 40s. These regimes in turn used these caricatures to legitimize the persecution of Jews that they then put in place.

While today we cannot expect to see this same kind of representation of Jews in traditional media, antisemitic caricatures continue to be massively propagated via social media and online memes, sometimes without the user being aware. Yet still other times, users have nefarious intent and share these images to propagate hateful messages. Moreover, we have seen mainstream media publications still publish antisemitic caricatures to this day. The echoes of the Jewish “globalist” “banking” “all powerful” “capitalist” conspiracy theories continue to evolve and mutate and are ever present in our current political discourse.

Antisemitism is still very much a present-day reality, and it is important to recognize the means by which it is expressed in order to be able to better denounce and deconstruct it.

Text written by Étienne Quintal, researcher at CIVIX, and the Montreal Holocaust Museum

LEARN MORE

To delve further into the history of antisemitic caricatures, listen to Holocaust survivor Fishel Goldig’s testimony about antisemitism and discover Dolores Rosen’s Cane. You can use our Artefact and Testimony Analysis Sheets with your students to analyse these primary sources.

Antisemitic caricatures are still seen in media today and frequently as memes online. Hatepedia, a guide to online hate, describes many of them in its various sections.

Bibliography (in French only)

On antisemitic caricatures in Europe :

- Matard-Bonucci, Marie-Anne. «L’image, figure majeure du discours antisémite», Vingtième Siècle, revue d’histoire, n°72, octobre-décembre 2001, pp. 27-40. https://www.persee.fr/doc/xxs_0294-1759_2001_num_72_1_1410

- Doizy, Guillaume. « Édouard Drumont et La Libre parole illustrée: la caricature, figure majeure du discours antisémite ? », Cahiers d’histoire. Revue d’histoire critique, 135, 2017. http://journals.openedition.org/chrhc/5917

- Paissa, Paola. «Rires d’autrefois: le journal humoristique Le Rire en 1895», Bouquets pour Hélène, Publifarum, n°6, 05 février 2007. http://publifarum.farum.it/ezine_articles.php?id=41

On antisemitic caricatures in Québec:

- Leblanc, Jean-Pierre. «Brève histoire de la presse d’information au Québec», Centre de ressources en éducation aux médias, 2003. http://reseau-crem.lacsq.org/trousse/histoiremedias.pdf

- Desforges, Josée. «Entre création et destruction : les comportements des types du Juif et du Canadien français dans les caricatures antisémites publiées par Adrien Arcand à Montréal entre 1929 et 1939», Mémoire de maîtrise, UQAM, 2012. https://archipel.uqam.ca/5248/1/M12740.pdf

On social media and racist and supremacist discourse :

- Forcier, Mathieu. «Diffusion, radicalisation et normalisation des rhétoriques d’extrême droite sur Internet», Traces vol. 58-1, 2020, p.28-33

- Pinilla, K. (2022, May 6). From left to right: An overview of the “veiled” antisemitism threat landscape online. ISD. https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/from-left-to-right-an-overview-of-the-veiled-antisemitism-threat-landscape-online/