Between 1904 and 1908, more than 80% of the Herero population and 50% of the Nama population of Namibia were killed by German soldiers.

Situation before the genocide

In the 19th century, Namibia, a country in southern Africa, was populated by several ethnic groups: the San, Damara, Ovambo, Nama and Herero. The Nama and Herero, livestock farmers, were the country’s two main tribes.

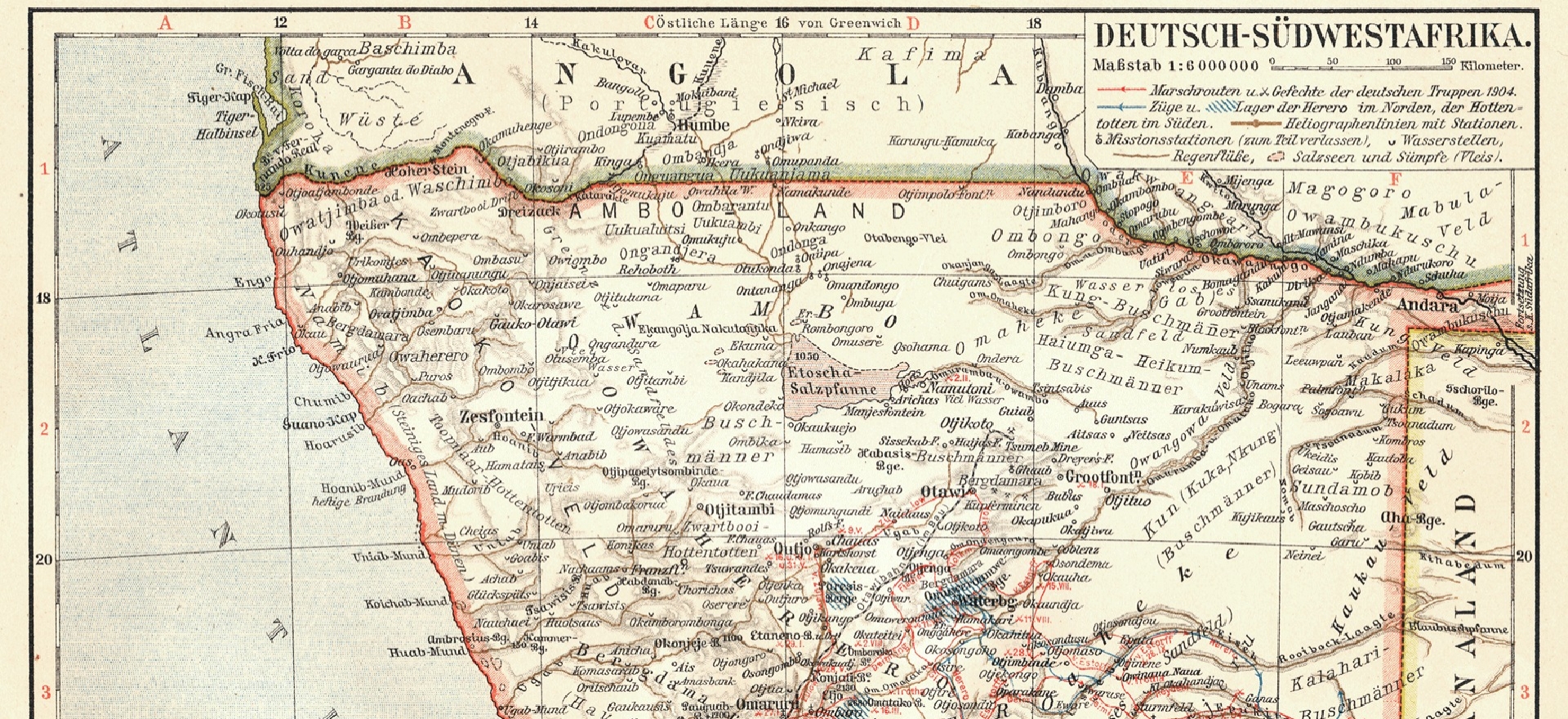

In 1884, Germany invaded the Namibian territory and founded the German South West Africa colony. The colonizers’ interest increased after the discovery of diamonds in 1894.

Genocide triggers

A policy of systematic land confiscation and the arrival of more and more German settlers forced the farmers off their land.

On January 12, 1904, the Herero rebelled. Guided by their leader, Samuel Maherero, they attacked a German garrison at Okahandja.

Progress of the genocide

In June 1904, the German General Lothar von Trotha was sent to Namibia to suppress the Herero revolt. He arrived in Namibia with 10,000 soldiers and a war plan.

On August 11, 1904, at the Battle of Waterberg, German soldiers encircled the Herero and were under the order to take no prisoners. A few thousand Herero nonetheless succeeded in fleeing to the Kalahari Desert. German soldiers poisoned the few waterholes and were under the order to fire on any Herero attempting to return to their land. In just a few weeks, thousands of Herero died of hunger and thirst.

The order to kill all Herero was signed on October 2, 1904 by von Trotha:

“The Herero are no longer German subjects (…). Any Herero sighted within the [Namibian] German borders with or without a weapon, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will no longer accept women and children, but will send them back to their people or let them be slaughtered.”

Herero who survived the desert were imprisoned in concentration camps and enslaved. Thousands of women were victims of sexual violence inflicted by German soldiers.

Dr. Eugene Fischer conducted medical experiments on children born from these rapes. His conclusion was that children born out of bi-racial unions were “inferior” to their German fathers. His research inspired Adolf Hitler and in the 1930s, Fischer taught his racist theories to Nazi doctors. One of his students, Joseph Mengele, was responsible for the medical experiments in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp.

After the genocide

After the First World War, South-West Africa was placed under South Africa’s administration. An apartheid system was created. As of the late 1940s, different groups fought for independence. In 1968, the United Nations recognized the name of Namibia and in 1990, the country finally gained its independence after South Africa’s withdrawal.

Recognition of the Herero genocide

In 1999, substantial mass graves were discovered in the Kalahari Desert. The Herero requested that the presence of victims’ bodies from the 1904 genocide be recognized. The Namibian government, anxious to maintain good relations with the former German colonizers, refused to recognize the site.

In October 2000, the first official meeting between the Herero and the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights took place. The genocide was on the road to historical recognition. In 2004, the German government acknowledged its responsibility for the genocide of the Herero, without granting them financial compensation. In 2018, Germany returned remains to Namibia but has yet to formally apologize.

Learn more about genocide

Go to the Shoah Mémorial website to visit the “Le premier génocide du XXe siècle – Herero et Nama dans le Sud-Ouest africain allemand, 1904-1908” virtual exhibition (in French only), which presents the Herero and Nama genocide in further detail.

You can learn more about the subject by reading our article The Ten Stages of Genocide, which outlines the identifiable steps that lead to genocide.

You can also visit our “United Against Genocide: Understand, Question, Prevent” virtual exhibition which takes a closer look at four genocides of the 20th century: the Armenian genocide, the Holocaust, the genocide in Cambodia and the genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda. The exhibition also provides the opportunity to learn more about four contemporary situations of escalating violence: Burundi, Iraq, South Sudan and Myanmar.

Visit the Virtual Exhibition