Between April and June 1994, an estimated 800,000 people were murdered in the Rwandan genocide. Although the genocide targeted the Tutsi minority, thousands of Hutu who opposed the military regime were also killed.

Historical Context

The Hutu and Tutsi were two very similar ethnic groups living in Rwanda; they shared the same language and cultural and religious traditions.

In 1916, Belgian forces took control of Rwanda, which up to that point had been a German colonial territory. Three years later, the Treaty of Versailles officially allocated Rwanda under Belgian rule. Using racist pseudo-scientific methods, authorities divided and created a hierarchy within the population based on physical differences. Based on measurements such as height, shape of nose, and skin colour, colonial authorities designated Tutsi as superior to Hutu. Access to education and administrative jobs was therefore reserved for this group only. These discriminatory practices led to an impoverished Hutu majority that developed resentment towards the Tutsi minority.

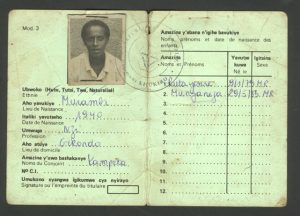

In the 1930’s, Belgian authorities implemented an official racial division by introducing identity cards that classified individuals as Hutu, Tutsi, or Twa. The policy contributed to the idea that ethnic and racial differences are rigid and naturally formed.

Rwandan ID card indicating that its owner is a member of the Tutsi ethnic group. Source : Kigali Genocide Memorial

In 1962, Rwanda gained independence with a Hutu leader in power. A year later, Tutsi rebels tried to overthrow President Grégoire Kayibanda’s regime. The regime managed to mobilize Hutu by capitalizing on their fear of a potential Tutsi tyranny. Kayibanda even referred to Tutsi as cockroaches. About 20,000 Tutsi were murdered and 300,000 fled the country. Those who remained in Rwanda were increasingly marginalized.

Civil War

From 1987-1988, exiled Tutsi living in Uganda formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a political and military movement. In 1990, approximately one million Rwandan Tutsi were living in exile. On October 1, 1990, the RPF launched an attack on Hutu President Habyarimana’s regime, an event which sparked the civil war. President Juvénal Habyarimama’s party, the MRND, formed the Interahamwe militia.

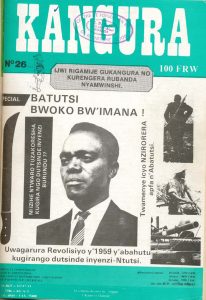

Published in both Kinyarwanda and French, Kangura (“Wake Up”) magazine was a driver of genocide, with articles published regularly spreading hatred toward Tutsis. Translation: “Tutsi: Race of God. What weapons can we use to defeat all these cockroaches once and for all?” Kangura magazine, issue number 26, November 1991.

On August 4, 1993, Habyarimana and the RPF signed the Arusha Accords in Tanzania, which ratified the end of the civil war and promised a safe return for refugees and the creation of a transitional government under UN supervision. The Hutu considered these agreements to be treasonous and called for the lynching of Tutsi. In December 1993, the plan to massacre Tutsi was set in motion and bourgmestres (village leaders) distributed weapons to Hutu citizens. The authorities launched a propaganda campaign that depicted Tutsi as a threat and incited violence against them their persecution.

Catalyst of the Genocide

On April 1994, an airplane carrying Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana and the President of Burundi, Cyprien Ntavymira, was shot down in Kigali. Immediately afterwards, the presidential guards launched a retaliation against opposition leaders, moderate Hutu, and the Tutsi population.

The Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda

The main organizers of the genocide came from Hutu Power, an extremist anti-Tutsi group founded in 1993 by close associates of President Habyarimana.

The genocide was carried out with the help of local mobilization efforts. Local officials rounded up Tutsi in various places (schools, churches) to facilitate group executions. The Hutu population participated in the massacres. The majority of victims were murdered with machetes. The government radio station supported the Interahamwe and broadcast the names and information of Tutsi and moderate Hutu.

Tutsi women were victims of systematic and public rape. Approximately 250,000 women were raped and two thirds of them contracted the AIDS virus.

The UN had been alerted several times of Hutu Power’s actions, including one warning made directly by the commander of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR). The mission had been operating under the command of Canadian Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire in Kigali since October 1993.

End of the Genocide

On July 4, 1994, the RPF seized control of the Rwandan capital, Kigali, and the Hutu army retreated to a secure zone established by the French. Two million Hutu fled to Zaïre (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Tanzania.

A new multi-ethnic government was formed on July 19, 1994, promising refugees a safe return to the country.

Aftermath

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established in Arusha in November 1994. The ICTR convicted 61 individuals for committing genocide and other crimes against humanity. It was the first international tribunal to recognize rape as a weapon of genocide and to prosecute members of the media for spreading propaganda that incited violence during the genocide.

Widespread public participation in the Rwandan genocide made it difficult to prosecute those who were guilty; however, more than 100,000 individuals were imprisoned in the years following the genocide.

Common courts had jurisdiction to try alleged perpetrators of the genocide. Rwandan authorities also set up gacaca courts, community-based tribunal systems that were centred around public confession. This form of traditional justice was seen as having contributed to the national reconciliation process.

Recognition of the Genocide

It was not until 1999 that the UN admitted its failure in preventing the genocide. An independent report, commissioned by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, denounced the organization for ignoring evidence of a planned genocide, refusing to intervene when the massacres began, and abandoning the victims.

To learn more

The Museum’s “United Against Genocide: Understand, Question, Prevent” online exhibit